India Going Global

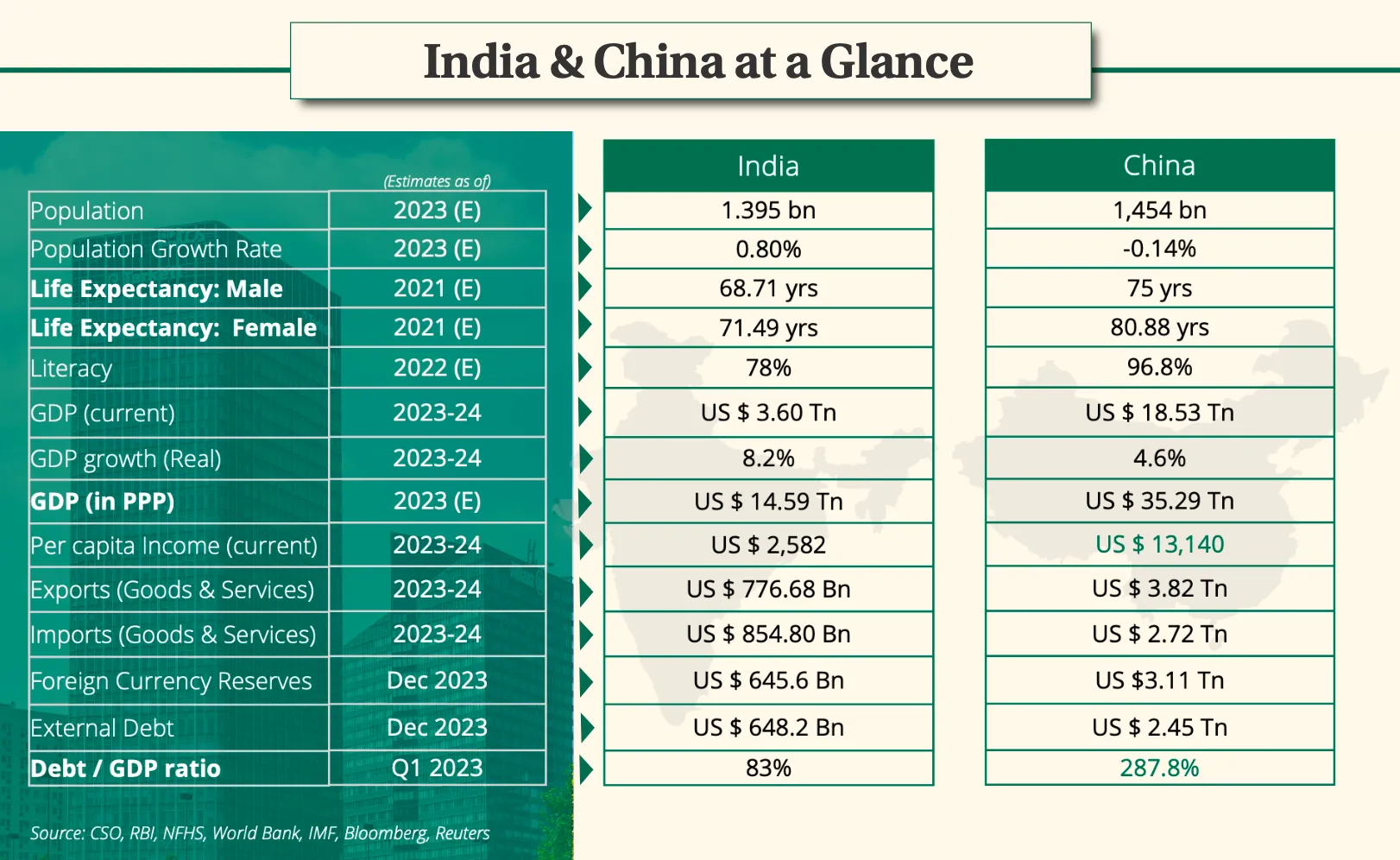

India is at a pivotal moment in its economic trajectory. In FY24, the country’s nominal GDP reached $3.7 trillion, solidifying its position among the world’s top five economies. In purchasing power parity (PPP) terms, India ranks in the top three, with an economy valued at nearly $15 trillion, trailing only China and the U.S. India is poised to surpass $5 trillion in nominal GDP, on its way to $10 trillion within the next fifteen-eighteen years, driven by favourable factors such as its young demographics, growing domestic consumption, open economic policies, and vital capacity for technological adoption.

India remains the fastest-growing large economy in the world and is meeting expectations on its path to $5 trillion and beyond.

India’s economic growth has been remarkable in recent years. The country grew 8.2% in the financial year 2023-24, building on growth rates of 7.2% in 2022-23 and 8.7% in 2021-22. This sustained strong performance has elevated India to the fifth-largest economy in the world, overtaking the UK in 2022.

The government has laid out an ambitious vision for India@100, aiming for a developed and prosperous nation—Viksit Bharat. As the global landscape shifts, accelerated by the pandemic and the post-pandemic quantitative tightening, India faces a once-in-a-generation opportunity to build economic and technological moats to help realise these aspirations. The real challenge lies in prioritising and supporting the right goals with the necessary policy frameworks and investments.

From Poverty to Middle-Income and Beyond

India needs to transition from optimising for topline GDP growth to higher income per capita.

The Indian economy has outperformed most large economies since its 1991 liberalisation. It has grown from a 1991 GDP of ₹5.32 lakh crore ($275 billion) to ₹272 lakh crore ($3.47 trillion) in FY23 and $3.7 trillion as of FY24. This translates to a robust CAGR of 13.08% in nominal rupee terms, and 8.24% in dollar terms over 33 years. No other country except China has achieved this tremendous feat, and India has laid solid foundations for its GDP leap forward from here. This economic growth has substantially reduced the level of higher and more extreme poverty in the country since 1991.

Between 2013-14 and 2022-23, over 248.2 million people in India escaped multidimensional poverty. NITI Aayog’s Discussion Paper, Multidimensional Poverty in India since 2005-06, attributes this achievement to key government initiatives and the active role in job creation by private industry in addressing all dimensions of poverty. The Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) is an internationally recognised metric that goes beyond monetary measures, capturing various aspects of poverty. Based on the robust Alkire and Foster (AF) method, the MPI identifies individuals as poor across various factors, providing a more holistic view of poverty than traditional monetary measures.

According to the Discussion Paper, India’s multidimensional poverty rate dropped significantly from 29.17% in 2013-14 to 11.28% in 2022-23—a reduction of 17.89%. Over the last nearly two decades, there have been substantial improvements in the quality of people's lives, with poverty levels declining sharply from more than 50% to 11.28%. India is all set to reach single-digit poverty levels during 2024. This progress positions India to meet its Sustainable Development Goal of halving multidimensional poverty well before the 2030 deadline.

“India’s trend GDP growth is currently at 6.5-7%. The population growth has been around 1%. This means that the per-capita income growth on a trend basis should be around 5.5 per cent, which is closer to the projected levels by the OECD-FAO report,” said Paras Jasrai, an economist at India Ratings & Research.

India is projected to lead the world in per-capita income growth, with an annual increase of 5.4% during the period from 2024 to 2033, according to a recent report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). India’s GDP per capita is projected to reach nearly $2,900 by 2024-25, marking substantial progress since surpassing the $2,000 mark in 2018-19. The anticipated inflection following the $2,000 milestone has indeed materialised, evidenced by increased discretionary spending, accelerated poverty reduction, and higher gross enrollment rates in education.

As India nears its 100th year of independence in 2047, the country’s per capita income is expected to rise to Rs 14.9 lakh ($17,570), according to a presentation by Chief Economic Adviser V Anantha Nageswaran. The Economic Survey for 2023-24 reports that the current per capita income stands at Rs 2.12 lakh ($2,500), more than doubling over the past decade. This growth underscores the tangible benefits of India’s rapid economic expansion and is a stellar achievement.

However, while India has grown admirably since 1991 and is performing reasonably well, it has been mostly organic with the lack of a long-term cohesive strategy to achieve the jump from $4 trillion to $10 trillion that every citizen can align behind. Business-as-usual (BAU) is insufficient to take India beyond the middle-income trap, and more focused strategies are essential to continue the momentum and deliver the same growth rate on an increasing base. Most importantly, for this topline growth to translate to better lives and livelihoods for all of its citizens, India now needs to optimise to grow income per capita as well.

Strategies to Escape the Middle Income Trap

Higher wages, not just the creation of jobs, is the final critical imperative.

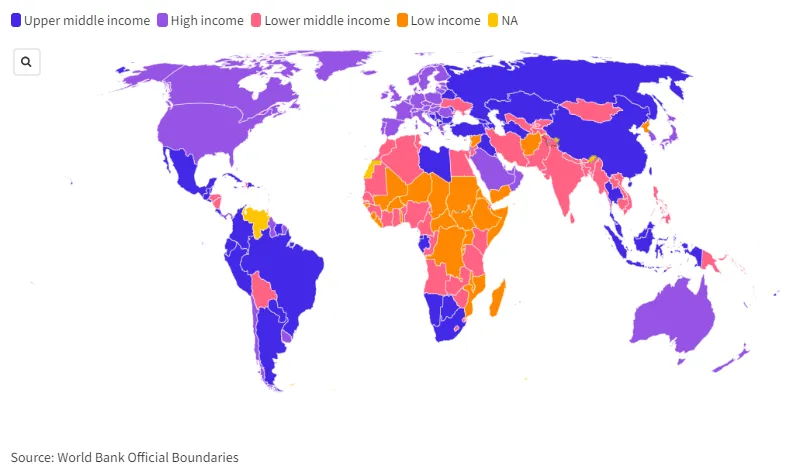

The middle-income trap occurs when a country reaches a middle-income level but struggles to progress to a high-income status. This often happens when wages become too high to remain competitive in labour-intensive industries while productivity remains too low to excel in higher value-added sectors. India and 108 other nations, such as China, Brazil, and Turkey, risk falling into this trap if they continue with a “business-as-usual” approach.

According to the World Bank’s 2024 World Development Report, these countries tend to face more severe information deficits than low-income and advanced economies due to the complexity of their economic structures. As a result, they are more vulnerable to the negative impact of policies based on simplistic economic efficiency measures, often leading to premature development slowdowns.

As of the end of 2023, the World Bank classified middle-income countries as those with a gross national income (GNI) per capita between $1,136 and $13,845. While India is projected to surpass a per capita income of $17,570 by 2047, it must proactively avoid the middle-income trap to ensure it reaches this target and delivers prosperity directly to its citizens.

The 3i Strategy To Escape The Middle Income Trap

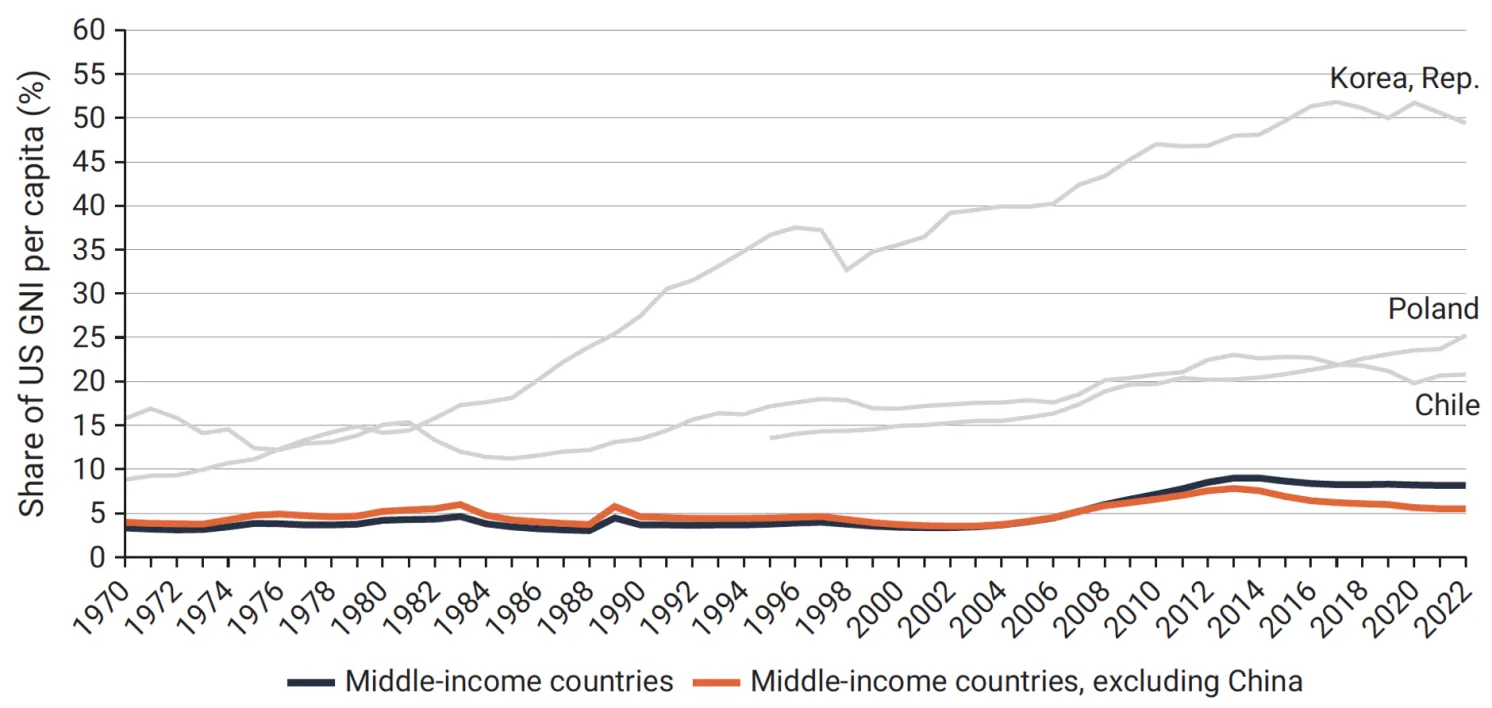

The World Bank asserts that middle-income countries' growth potential hinges on their ability to boost production through innovation—a challenging task for many economies to scale effectively. The report further notes that reaching high-income status could take several generations for many middle-income nations if current growth rates persist.

Over the past few decades, only a handful of countries, including Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Hong Kong, and South Korea, have successfully transitioned from middle-income to high-income status.

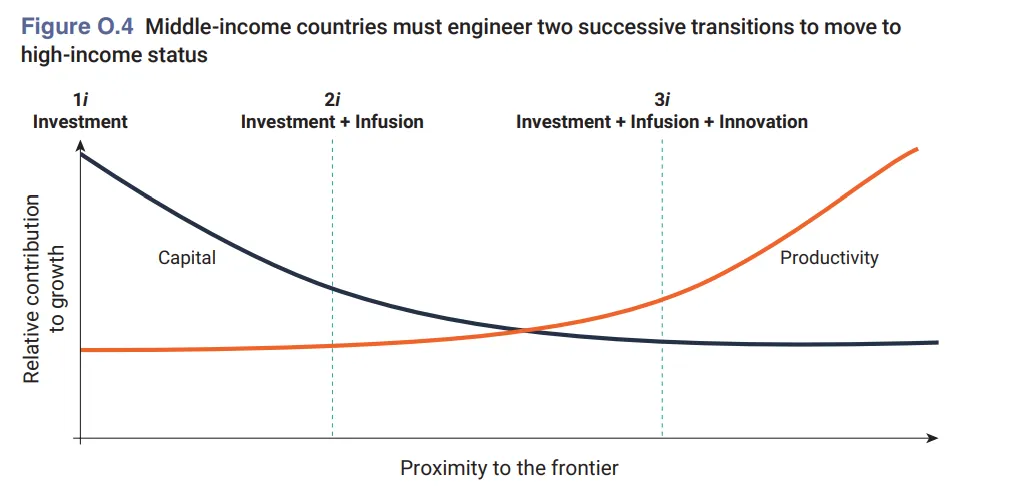

To help countries avoid the “middle-income trap,” the World Bank proposes a three-pronged strategy known as the “3i strategy.” This approach focuses on a strategic alignment of economic policies centered around:

- Investment

- Infusion of capital

- Innovation

To develop more advanced economies, middle-income countries must undergo two key transitions. The first transition, primarily for lower-middle-income countries, involves combining investment with the infusion of modern technologies, focusing on imitating and disseminating these innovations. The second transition, relevant to upper-middle-income countries, adds innovation to the mix, enabling these nations to build domestic capabilities that enhance global technologies and eventually position them as innovators. Throughout their journey, middle-income countries must adjust the balance of investment, infusion, and innovation to sustain economic growth.

Korea’s Example - From 3i to Exports

In the 1970s and 1980s, South Korea implemented reforms aimed at encouraging private investment and promoting industrial policies that enhanced technology adoption and production efficiency. The country then shifted to an export-driven strategy, focusing on expanding the market share of its largest enterprises in the world’s most advanced economies. The resulting economic growth was remarkable, with South Korea’s per capita income soaring from $1,200 in 1960 to $33,000 by 2023.

The few economies that have successfully and rapidly transitioned from middle- to high-income status have done so by fostering competition through checks on powerful incumbents, nurturing talent by rewarding merit, and leveraging crises to reform outdated policies and institutions. India will need to follow a similar path to achieve the same success.

India’s Progress on 3i

India is progressing quickly through a real-time multiplexing of the 3i strategy. While the country has made radical progress on all three fronts, more focused policy and structured incentives can accelerate India’s growth trajectory using the 3i framework.

Investment

India is one of the few countries worldwide investing $1 trillion+ annually in the economy, government, and private sectors combined via gross capital formation. This amounts to a significant 31% of the nation’s GDP. Significant investments have been made to boost trade activities and increase the capacities of India’s ports, airports, freight, railways, and other critical aspects of trade-related logistics. The trip from Bangalore to Delhi previously took four days, now it’s possible in two. Goods carriage speeds have exceeded 45kmph, from an average of 25kmph earlier. The Dedicated Eastern and Western Corridors for exclusive goods movement up and down the country have been game changers. Between GST and infrastructure development, supply chain costs are reducing from 14% of GDP to 8-9%.

Apart from improving the infrastructure itself, measures like electronic sealing of containers, electronic submission of supporting documents with digital signatures, machine-based automated clearance of imported goods and use of handheld devices for on-the-spot clearances have been taken to improve port operations and reduce turnaround times. Investment is now leading to tangible productivity gains across sectors nationally.

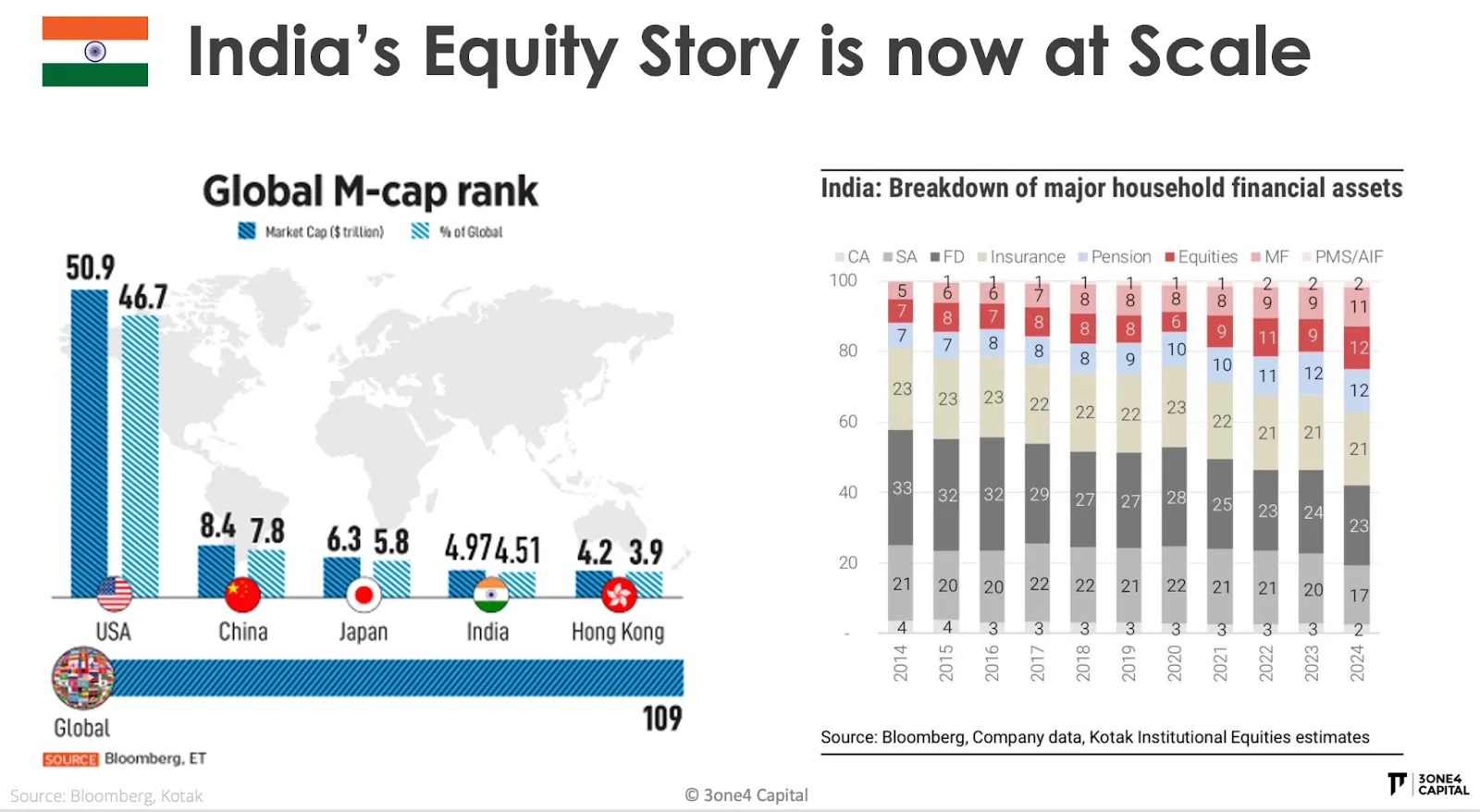

India’s stock market has overtaken Hong Kong’s to rank as the fourth-largest equity market globally. Fifty-four days after reaching a $4 trillion equity market capitalisation, India’s capital markets ascended to the fourth spot globally in January 2024, surpassing Hong Kong. This advancement marks India's continued ascent in the global stock market rankings, having previously overtaken both France and the UK in June 2023, positioning it behind only the US, China, and Japan. As of Aug 2024, India’s total market capitalisation stood at $4.97 trillion.

The inbound local liquidity of $4 billion monthly from SIPs, pension programs, and institutional allocations has provided a reliable substrate of support for the Indian markets. Even though net FII was outward in 2023, Indian markets have had some of their best quarters yet. The mass financialisation of household savings is underway, with household financial assets doubling their share in mutual funds and equities over the last decade.

Infusion of Capital

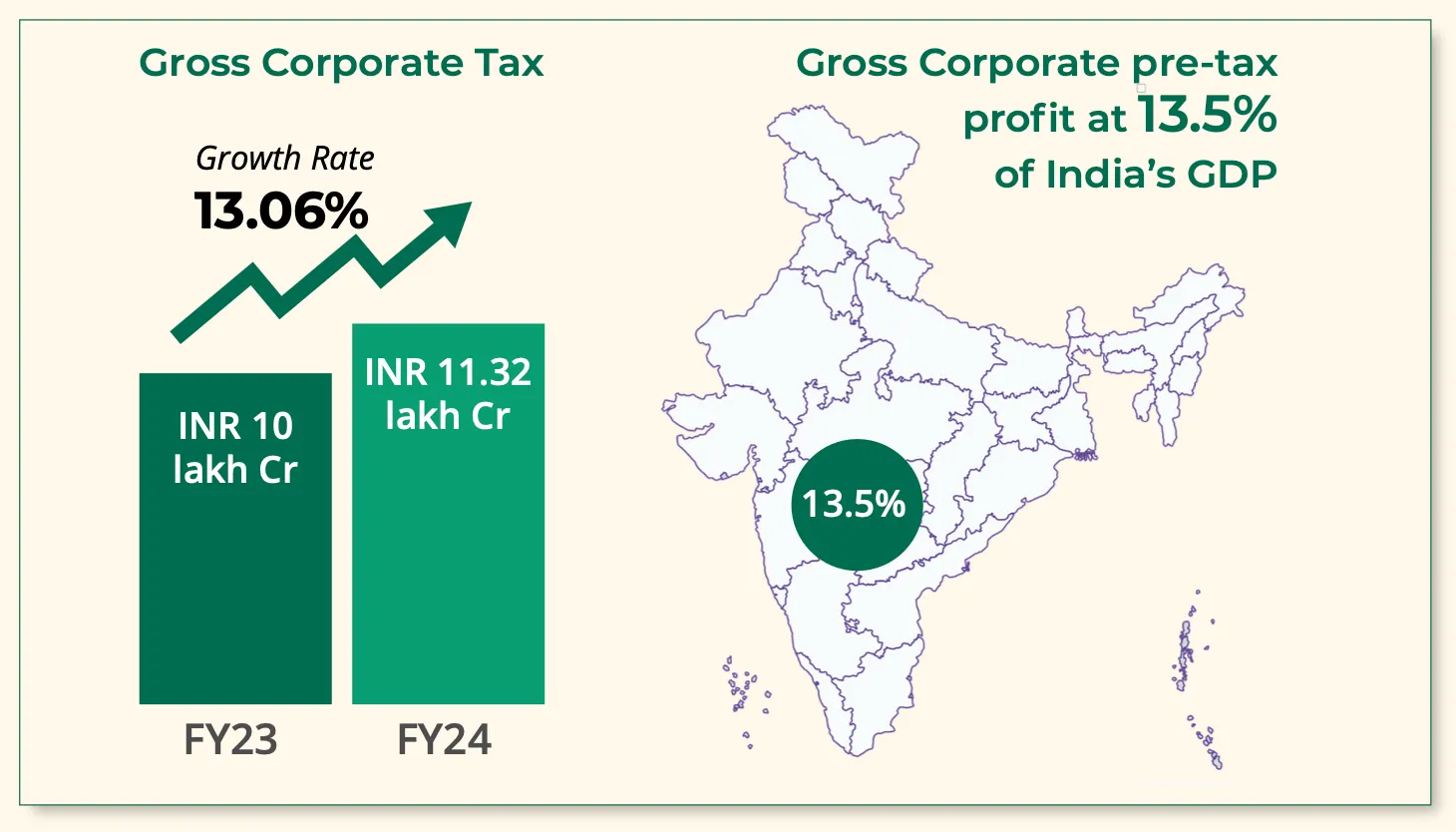

Indian corporates recorded their highest profitability at 13.5% of India’s GDP over FY24 (INR 45.28 lakh crore of pre-tax profits over FY24). This staggering statistic explains the tidal force underneath the Indian capex cycle underway. As India Inc. pays down its debts from its free cash flows, it is also allocating capital to new projects and aggressively expanding capacity.

We are already witnessing heightened interest in India in 2024, with significant inflows into the country's bond and equity indices. Inclusion in the JP Morgan EM Bond Index and the launch of new passive funds tracking Indian Nifty Indices signal a substantial shift. The total AUM of such funds has surged from USD 1 billion in November 2013 to around USD 70 billion in November 2023, presenting a compelling investment landscape. This influx is expected to lower interest rates, and private investors, previously inactive, are set to redeploy from September 2024, creating favourable investment opportunities.

Morgan Stanley reports that India's capital expenditure (capex) cycle is experiencing a resurgence, reminiscent of the growth seen during the 2003-2007 growth period. The analyst projects that by 2027, India's investment as a percentage of its gross domestic product (GDP) could reach 36%, fueled by public capital expenditures, increasing exports, and a stable economy. This mirrors the trend from 2003-2007, when the investment ratio in India peaked at 39%.

India Inc. sees higher profitability, an increase in private capex is anticipated, and an increased flow into bonds which could elevate the overall investment to target 40% of GDP.

Innovation

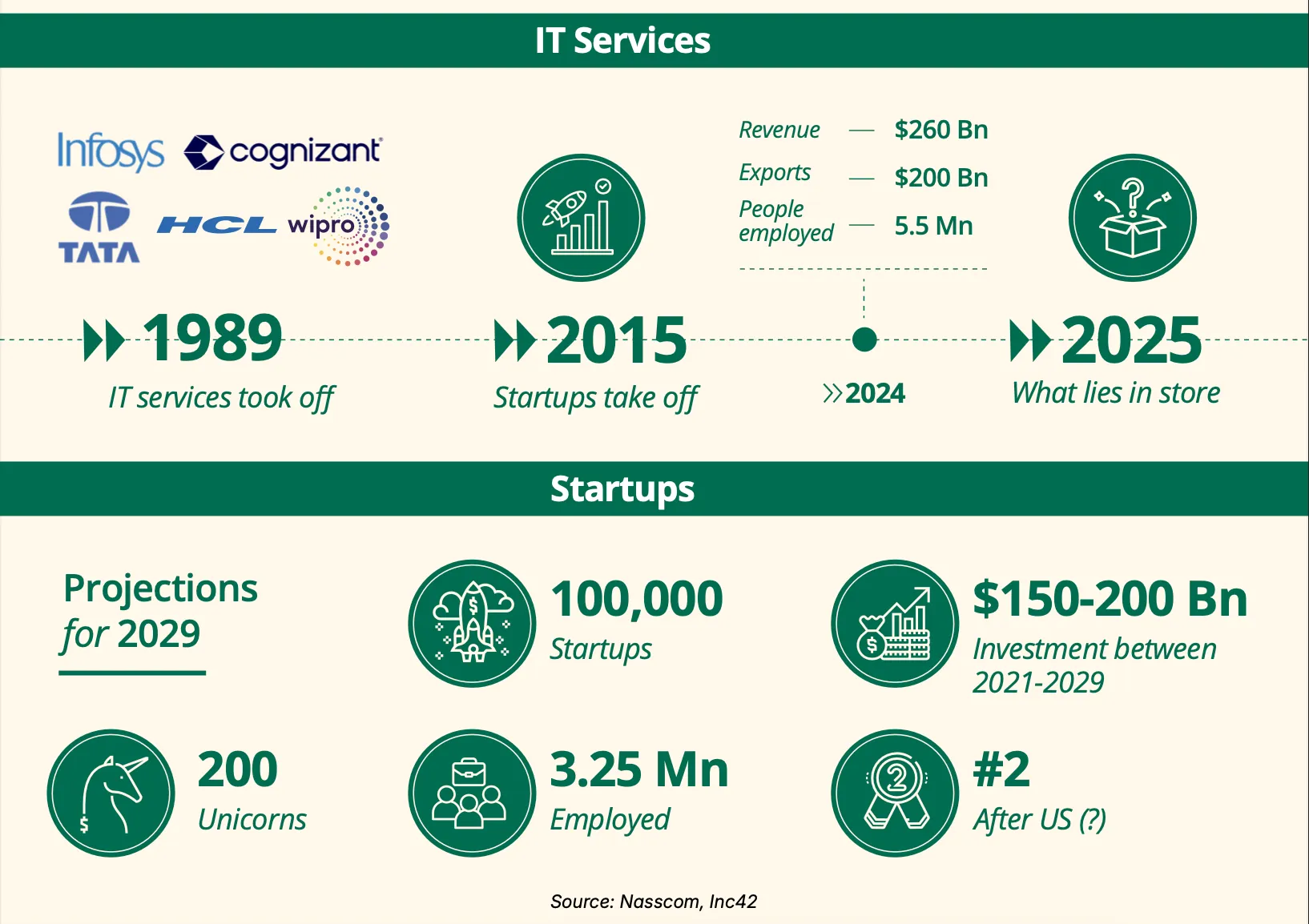

India already hosts the third largest startup ecosystem in the world after the US and China. Analyst reports show that while $136 billion entered the Indian startup ecosystem between 2014 and 2022, this number pales compared to the $837 billion and $2.7 trillion that entered the Chinese and US ecosystems, respectively, during the same period. India now has 116 unicorns, also the third highest globally. Now, India is ahead of many developed economies such as the UK (~50 unicorns) and Germany (<40 unicorns).

The total value created by the Indian startup ecosystem has crossed $450 billion, and estimates suggest it may reach $1 trillion by 2030. There have been 30+ tech IPOs completed already, with at least 30 more having filed and in the pipeline. Over $90 billion has been returned via exits cumulatively across Indian PE-VC just between 2021 and 2023. The past three years have seen India’s PE-VC ecosystem go from strength to strength, experiencing an exceptional bullish run with more than $60 billion in deal value unlocked each consecutive year since 2020. The major positive shift that has happened here is that Indian startups can now aim for an Indian IPO to continue their growth story as listed companies.

While private sector innovation and the startup ecosystem have delivered extraordinary gains over the last decade, more research and education institutions-led grants are required to sustain the foundations of Indian innovation.

Exports and 3i Together - India’s Leap Forward

India and China have followed vastly different paths in their economic development since the 1980s, with China’s approach yielding faster GDP growth and higher per capita income. This divergence offers valuable lessons for India as it seeks to elevate the income levels of its citizens.

In the 1980s, the two countries had comparable economies, with India even having a higher per capita income than China. However, by 2024, China has significantly outpaced India in terms of GDP size, per capita income, and global export share.

According to IMF data, China’s economy in 2024 is valued at $18.53 trillion—almost five times larger than India’s $3.6 trillion. Since 1980, China’s GDP has grown by a staggering 61 times, from $303 billion to $18.53 trillion, while India’s GDP has increased over 19 times, from $186 billion in 1980 to $3.6 trillion in 2024.

Under the NDA government in the past decade, India’s economy has grown by 93%, from $2.04 trillion in 2014 to $3.6 trillion in 2024. In contrast, China’s economy grew by 76% during the same period, from $10.5 trillion to $18.53 trillion. Under the UPA government from 2004 to 2014, India’s GDP surged by 188%, compared to China’s remarkable 440% growth during the same timeframe.

As of 2024, China’s per capita GDP-PPP of $25,015 is approximately 2.5 times higher than India’s $10,123. This marks a sharp shift from 1980, when India’s per capita income of $582 was nearly twice China’s $307. Over the past four decades, China’s per capita income has grown 82 times, while India’s has increased only 17 times. In the last 10 years alone, India’s per capita income has risen by 95%, while China’s has doubled in the same period.

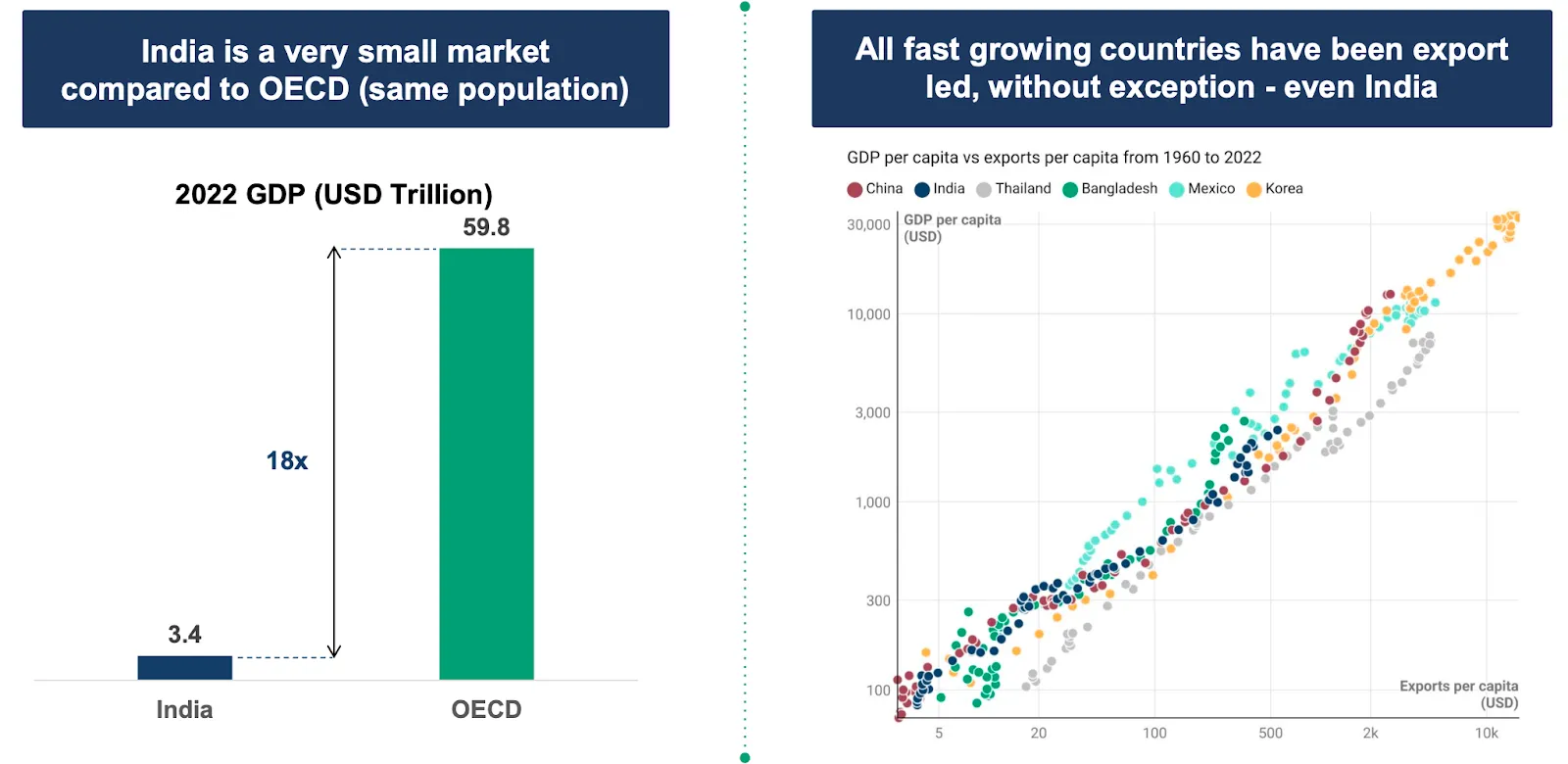

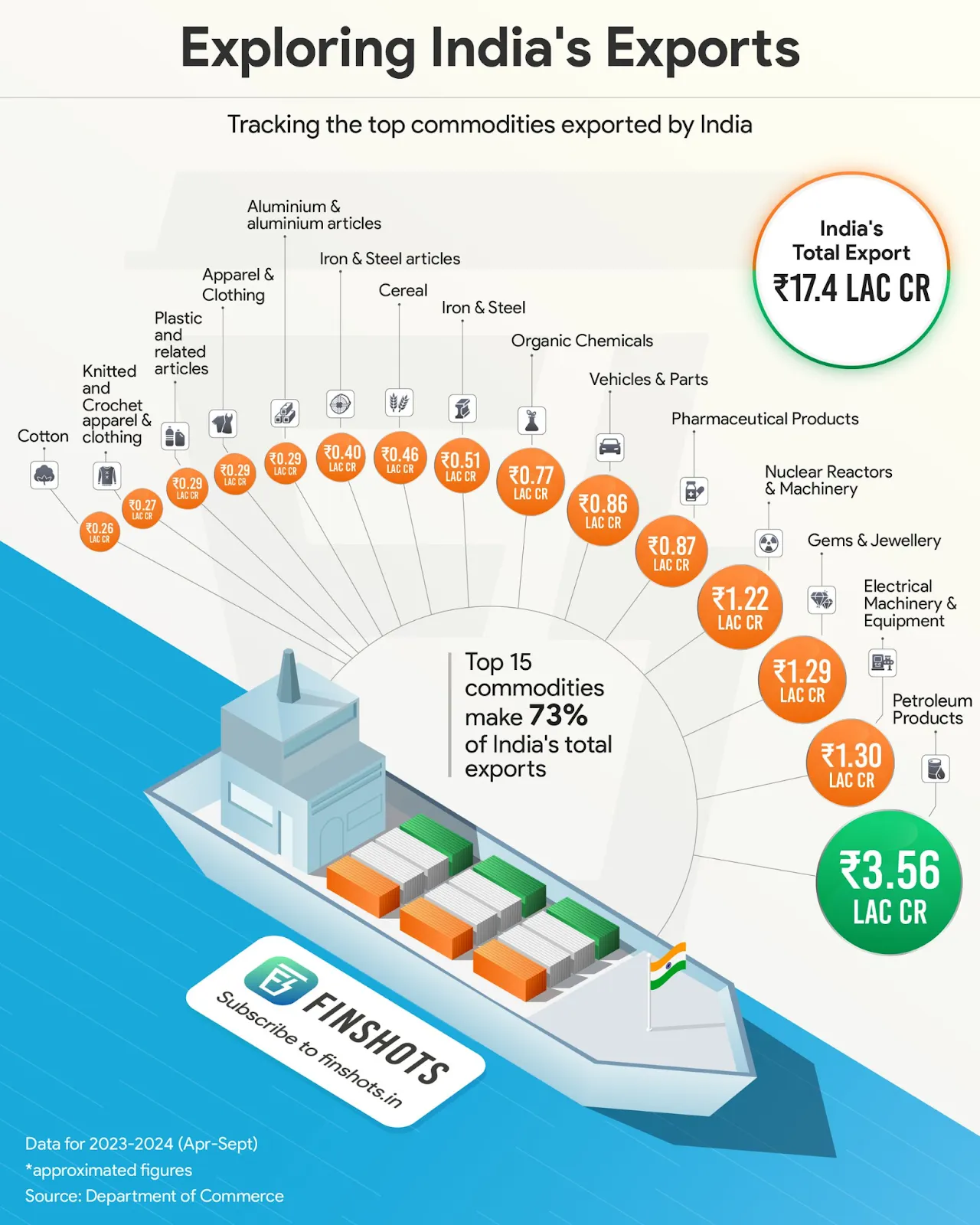

On the global stage, China is the world’s largest exporter, with $3.5 trillion in exports in 2023, accounting for nearly 14% of global trade. India, by comparison, is the tenth-largest exporter, with exports valued at $0.78 trillion—about one-fifth the size of China’s exports. This is the critical lever for India to build for itself - one that can deliver a sharp increase in income per capita as its topline GDP continues to grow.

Exports Will Increase Sophistication of Processes and Products

Exports will also help deliver larger TAMs and faster growth in incomes.

To achieve high-income status, a middle-income country needs to ramp up the sophistication of its economic structure. Using the economic complexity of a country’s export basket—a measure of sophistication—there is a rising relationship between sophistication and income for all economies that transitioned from a GDP per capita of less than $13,000 to more than $31,000. Exports, therefore, are critical to India’s leap forward.

Historically, every large low-income country that has transitioned to middle or high-income status over the past 75 years—such as Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, and China—has achieved this by focusing on exports. Even China, despite being larger than India, relied on global markets to fuel its rapid growth. Similarly, India’s own rapid growth in IT services was driven by exports to the world’s largest markets. This is why it is crucial for India to look beyond its borders and target larger global markets.

However, India has struggled to achieve the same success as its services exports in labour-intensive manufacturing exports, where it should have a significant advantage. Growth in this sector could have benefitted those who needed it most, helping accelerate income growth.

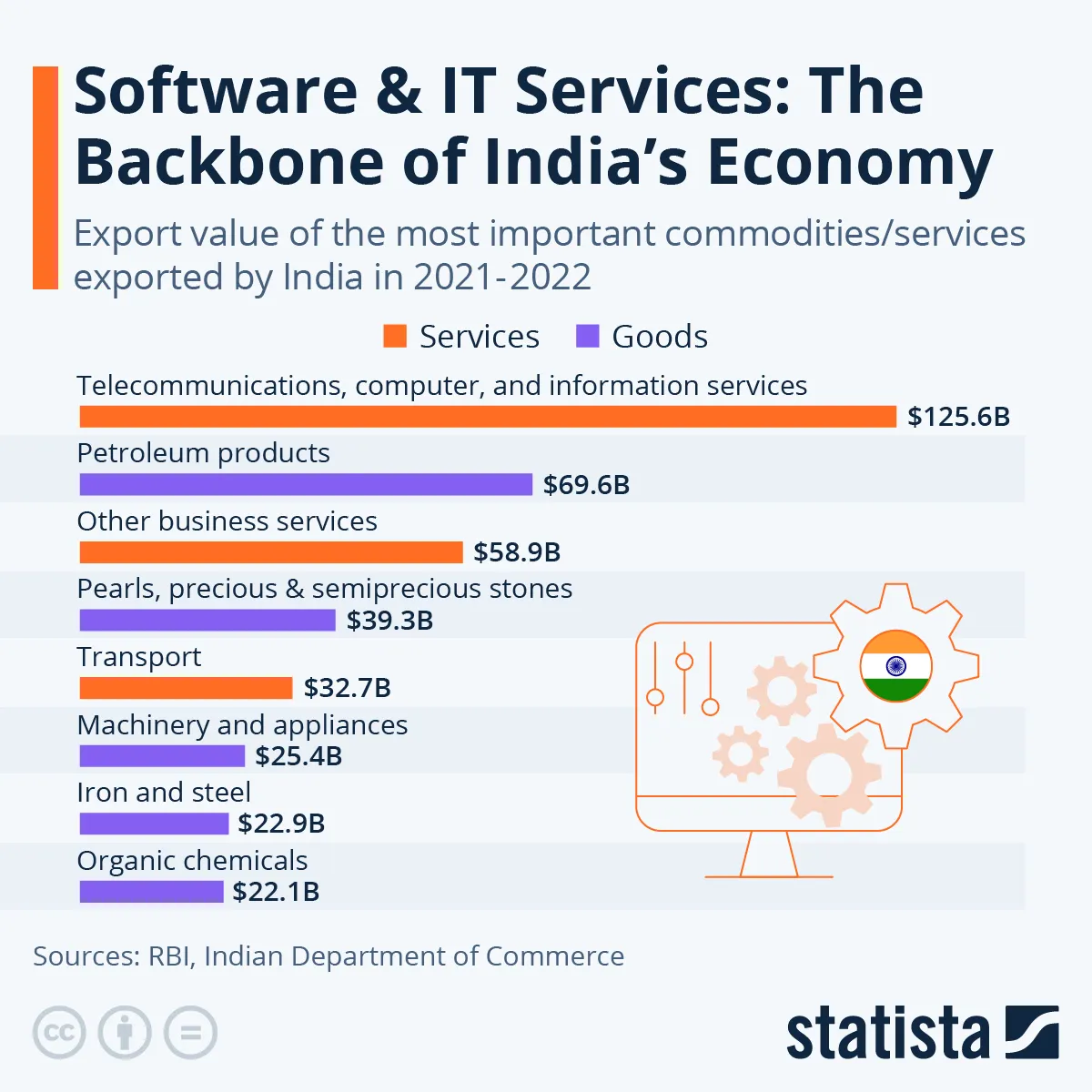

India Inc. has to take cues from the export success stories of China, Japan, and South Korea, and extend global competitiveness and market share across international markets. The goods exports vary a spectrum of commodities, from Petroleum products and Pharmaceuticals to Chemicals and Gems & Jewellery. The country must invest more to grow its exports in every vertical by 10-15% per year to accelerate the economic benefit of higher prices, job creation, and wage increase. India is already capable of demonstrating leadership in services exports, with the Indian Information Technology industry as a standout example of this innate capability.

Beyond its strengths in IT, business services, and pharmaceuticals, where it excels, India must broaden its export portfolio by boosting exports in textiles, apparel, and footwear, along with expanding into electronics and green technology products. Focusing on labour-intensive industries particularly will help create higher wage jobs as well.

IT services were successful because our legacy of laws and institutions did not anticipate their nature or promise of success. Policy friction to scaling manufacturing remains, and export-led manufacturing has to become a national priority. Our political and industrial leadership must work together to create laws and institutions that support India's competitiveness in the world market.

Fortunately, the NDA government has recognised the critical role of exports, setting ambitious targets for various sectors and actively negotiating trade deals—both positive developments. However, these targets and agreements will only translate into tangible results if India dismantles the complex web of regulations that hinder Indian industries from operating and competing effectively on the global stage. With large strides being made in Ease of Doing Business (EoDB) every year, a more focused unpeeling of this complexity will unleash India’s best and brightest to compete and win globally.

Indian IT - Role Model for the Future of Indian Exports

India's technology and innovation ecosystem are built on the strong foundations of the IT industry. Originating as a services business in the 1980s, it has evolved into a leading export force, contributing significantly to India's global standing.

The Indian IT industry delivered a combined revenue of $260 billion over FY23, with over $200 billion in services exports. Employing over 5.5 million people, this industry has not only balanced the Indian central bank's USD reserves but also positioned Indian companies among the top global IT players.

This industry is India’s strongest competitive advantage - it will help reduce the balance of payments and strengthen the currency. India's current account deficit (CAD) dropped from $17.9 billion (2.1%) in Q1:2022-23 to US$ 9.2 billion (1.1% of GDP) in Q1:2023–24. As India’s IT, engineering, and services exports continue to grow, startups can also accelerate this important shift and contribute positively to build a structural advantage for the economy.

Startups can follow the example of Indian IT, and contribute to the acceleration of Indian exports across goods and services. This will strengthen the large and positive virtuous cycle of the 3i framework and help India deliver tangible growth in prosperity to every citizen as the economy grows into its $10 trillion GDP target.

India’s Manufacturing Export Successes

India has steadily built up production capacity in manufacturing towards exports. Smartphones have surged to become India’s largest product export to the US by value over the last three quarters, having overtaken diamonds. In AMJ FY25, smartphone exports exceed $2Bn, ahead of non-industrial diamonds at $1.44Bn. This shift first occurred in OND FY24 when smartphone exports to the US reached $1.42Bn and kept growing quarter by quarter. In JAS FY24, just a year earlier, smartphones were only the fourth-largest export from India to the US, showing swift expansion into one of the largest export markets in the world, by demand and value. Encouraging as this growth trend is, India still represents a relatively small export share of the US smartphone import market. In 2022 and 2023, the US imported $66Bn and $59.6Bn worth of smartphones, respectively. Beyond smartphones, it imported $55Bn and $46.3Bn worth of tablets and laptops in those years, mostly from China and Vietnam. The scope for growth and market capture in these segments are significant, and India must ramp up its investments, production and export policies accordingly.

Defence exports reached a record high in FY24 at ₹21,083 crore, marking an increase of 32.5% over FY23. There is a healthy involvement from both the private and public sectors, with Defence Public Sector Undertakings contributing 40% to the production value. Indian defence manufacturing is steadily moving up the value ladder. Ten years ago, low value items like munitions and bullets formed the bulk of exports. Today, with manufacturing successes like the Brahmos missile, Tejas fighter aircraft, and aircraft carriers, the value-add of defence manufacturing and exports are on an upward trajectory.

MSMEs are a critical piece of the Indian export puzzle. NITI Aayog estimates MSMEs account for 45% of the nation’s total exports and 38.4% of the total manufacturing output while providing 11 crore jobs—contributing to 27% of India’s GDP. Both exports of manufacturing and services are skill intensive. India’s specialization has become more skill-intensive in exports of auto and auto parts, electronics, machinery, pharmaceuticals, and defense. Lower down the value chain, India has not fully exploited the Lewis curve in its transition from a traditional economy to an industrialized and modernized one. Especially given its population, India has come nowhere close to capitalizing on low-skill exports including garments, toys, and footwear. MSMEs must be empowered to boost their manufacturing capacity to India can compete with Vietnam, Bangladesh and China, which continue to lead exports in this category.

India must study China’s export model to replicate its success. China has built the most successful labour-intensive industry-linked export sector globally. In 2023, China’s exports were valued at $3.4 trillion or ₹281 lakh crore—almost India’s GDP. The top 10 exports were electrical machinery and equipment, machinery including computers, vehicles, plastics and plastic articles, furniture and bedding, articles of iron and steel, toys and games, knit or crochet clothing and accessories, organic chemicals, and other clothing and accessories. Indian MSMEs already operate in these sub-sectors and can be encouraged to grow into export powerhouses with integrated policies and incentives nation-wide. India must adopt an economies of scale mindset to dominate these markets.

Special Employment Zones

India has already capitalised on its intellectual power and the network effects of the internet to build a globally competitive software services ecosystem. The startup ecosystem has risen on the backs of this ecosystem, demonstrating the feed-forward nature of hosting world-class economically beneficial ecosystems. Now, India must do the same to capitalise on one of its largest competitive advantages—its demographic dividend—to dominate world export markets. There is a need to broaden job availability by utilising the phenomenal work undertaken with the social schemes and infrastructure development over the last nine years. The Atma Nirbhar Bharat movement, Production Linked Incentive schemes, Make in India and Skill India initiatives, and export-linked manufacturing plans all provide a robust foundation to launch a country-scale employment generation movement. It is suggested that these be established as Special Employment Zones (SEZs) – a vision to create five crore new jobs in India’s heartland over five years.

Substantial annual budget allocations are required to achieve this vision. The allocation will be used to develop industry clusters, incentivise employers to set up factories there, and the complementary urbanisation required to make the clusters globally competitive. It is expedient to locate these clusters in labour-surplus regions. The scheme can identify 300 of India's backward districts and 1,000 tier 2/3/4 towns across the country, establish these clusters close to them, and provide the connectivity for the workforce to commute freely as well as the rapid movement of goods and materials to and from the country's arterial networks.

Tax deductions can be offered to entities registering in these SEZs, covering 130% of salaries and wages paid for employees residing in the neighbouring towns and districts for ten years. The Kaushal scheme can be incorporated for skilling and to verify salaries and wages via payment towards EPF or ESI. Women, who may not be able to commute or relocate as freely as men, can now find suitable employment close to their homes and fully engage in the economy, thereby increasing their workforce participation significantly. The SEZ mission will promote large-scale job creation in India's heartland, enabling backward districts to grow faster than their states, and creating a new growth engine in the country.

India is today the fifth largest economy and well on its way to becoming only the third economy to transcend the $10 trillion GDP ceiling after the US and China. This is the decade where we will see a surge of globally-aligned Indian value creators that will support the country's ascent towards becoming the third largest economy globally. Export orientation and technological productivity are two pillars of India’s 21st-century growth engine, and policy is now firmly behind the ecosystem to direct its growth towards the inclusive prosperity of its citizens.

.webp)